All mothers, of various ages and races, from every corner of Los Angeles County: From the middle class suburbs of the San Fernando Valley, to the hip, laid back Westside, to two of us from the working class South Bay.

Although we were all drawn there by the promise of a few dollars for a couple of hours of our time, answering a few questions for market research, once we introduced ourselves and began to tell our stories, a feeling washed over the room that women like us rarely feel.

We realized that we were surrounded by people that we didn't have to explain ourselves or our children to. When you have multiple children with ADHD, isolation is the norm, and you get used to it. With each answer to each prompt, every time another one of us told a story of dealing with multiple doctors and their varying opinions, of school teachers and administrators only too ready and willing to write a child off, of struggling with the unknown, then the search for answers once you found out what you may be dealing with, you could feel the breeze from all of the other heads nodding in agreement. We all knew all too well what each other was going through. We had all been there at one time or another.

We had all felt the sense of panic of knowing there was something not quite normal about our children I would watch my son exhaust himself, and everyone else, racing from one activity to another, never staying with anything for long. Or if there was nothing else to do, he would just crawl around in endless circles on the floor, completely freaking me out. I had heard of ADHD, but hadn't really done much research on it when I took him with me to a research study appointment at UCLA. The research assistant quietly observed him for the length of the appointment, then gently suggested that I bring him to be screened for another study they were doing on a medication for children with ADHD. I spent the next month or so reading everything I could get my hands on about ADHD, and the writing on the wall could not have been any clearer. I was prepared to put in work, because this was not going to be easy.

We talked of diagnoses, and the medication merry-go-round. All of us had gone through a minimum of two medications and multiple doses before hitting on that perfect combination that worked. Then realizing, for those of us with more than one child with ADHD, that the same magic combo that worked for Child One was highly unlikely to work for Child Two. There is the ultimate juggling act of keeping up with Doctors, appointments, meds, school-related issues (and believe me, there are many), and the sneaking health issues that come up on the side. Two of us have children that are perpetually underweight, (inviting scrutiny from the pediatricians) both because they are naturally small people, and because the prescribed medication kills their appetite.

We knew each others stories, and when the facilitator stepped out of the room, the relieved laughter started. We were finally with other women that weren't judging us because our kids weren't hitting all of the same milestones at the same time as other kids. And that was okay. We could admit that while we loved our children, we were glad to be away for a little while. These kids require exhaustive micromanagement, and although this is entirely doable, none of us kid ourselves. These children are WORK, with a capital W, and it gets tiring. Not that we don't love our children, obviously we do. We were just realistic about the demands on our lives.

As we were leaving, a few of us talked on the way to the elevator. It was nice escaping for an hour or so, and making a little extra cash to cover the endless extra expenses associated with child-rearing. It was also nice to decompress from always having your guard up when talking about your children. No Judgy McJudgerson mothers here, ready to alternately snark or condescend at the mere mention of difficulty, or the slightest indication of any small triumph. The mother next to me was happy not to have to say "No" for an hour, and planned to extend her time away to the actual time she said she was going to be home by making a solo trip to the mall. Not to buy anything, mind you. Just for the quiet time alone. We all understood perfectly.

This is the way of the parent of the child that needs a little more parenting than average. There is always one more: one more teacher to talk to, one more form to fill out, one more evaluation to complete, one more medication to convince them to try. It is a train in constant forward motion, often speeding, that just might change directions on a dime, frequently. And as a parent, it's all you can do to try to keep the train on a set of tracks, any tracks, long enough to complete a trip. All the while keeping your own train on track, just barely.

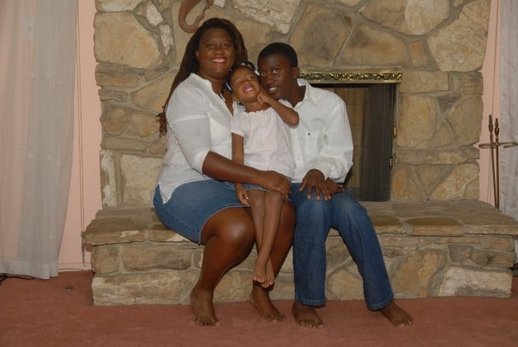

My son, my daughter and I all have some level of ADHD. My daughter is the only person on any type of medication for it, as my son refuses to even consider it anymore, and I figured out how to deal with the worse parts of it before I knew what it was. Not to say that any of us deals with it all particularly well, but we deal. I finally admitted to myself once my daughter started elementary school that anything not written down was lost, and Google Calendar was a Godsend for a person who consistently forgot about appointments. A friend taught me years ago how to create simple budgets that tracked where my money was going, and once combined with budget tools provided by my bank, I finally got control of my finances. I am still broke all the time, but at least now I know where it all went.

My son has good intentions, but is struggling. Even if he remembers daily tasks (going to class), details (assignments and due dates) escape him, and he refuses to write anything down. I understand that he wants to live without what he sees are crutches, but my role in this is to make sure that he realizes that real men DO get help when they need it, and there is no harm in admitting that you can't do everything by yourself. He is also dealing with an LD related co-morbidity called Auditory Processing Disorder. Meaning that what people say, and what he hears are often two entirely different things. Oh the misunderstandings that arise from not hearing EXACTLY what was said! Just learning to double-check verbal instructions and directions, and just follow normal conversations, has been a hurdle that took years to overcome.

My daughter is an extremely intelligent ball of energy, and having learned my lesson with my son, I make an effort to stay on top of everything going on at school. Academically, there are no issues, but her occasional emotional outbursts, and out of left field health issues, keep me glued to my phone during the day, as I never know when THAT phone call will come, and she will need to be picked up immediately. I find that teaching her to manage sudden change (and her emotions regarding those changes) is almost a full-time job. Anyone that has ever worked with a highly strung child will agree that having to be on your toes at all times gives you the balance of a ballerina after several years of managing these children's fragile emotions.

But we manage. All of us. The women in that room, and parents around the world that have children that for some reason or another, require just a bit more work that the usual amount. Especially when we ourselves take additional self management just to get through the day. We appreciate the little accomplishments because of the almost herculean effort it took to get to that point. We finally get a little something we can celebrate.

And for a brief hour in a conference room in West Los Angeles, we got a moment to let go of all of the work, all of the hassle, and all of the judgement, and just breathe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed